POODR by Sandi Metz Chapter Four

Book-Review: Chapter Four (Creating Flexible Interfaces)

DISCLAIMER/Acknowledement:

If there are any sentences or phrases that make a lot of sense to you then it was most likely copied word for word from Sandi’s book. She continues to inspire.

Finding the Public Interface

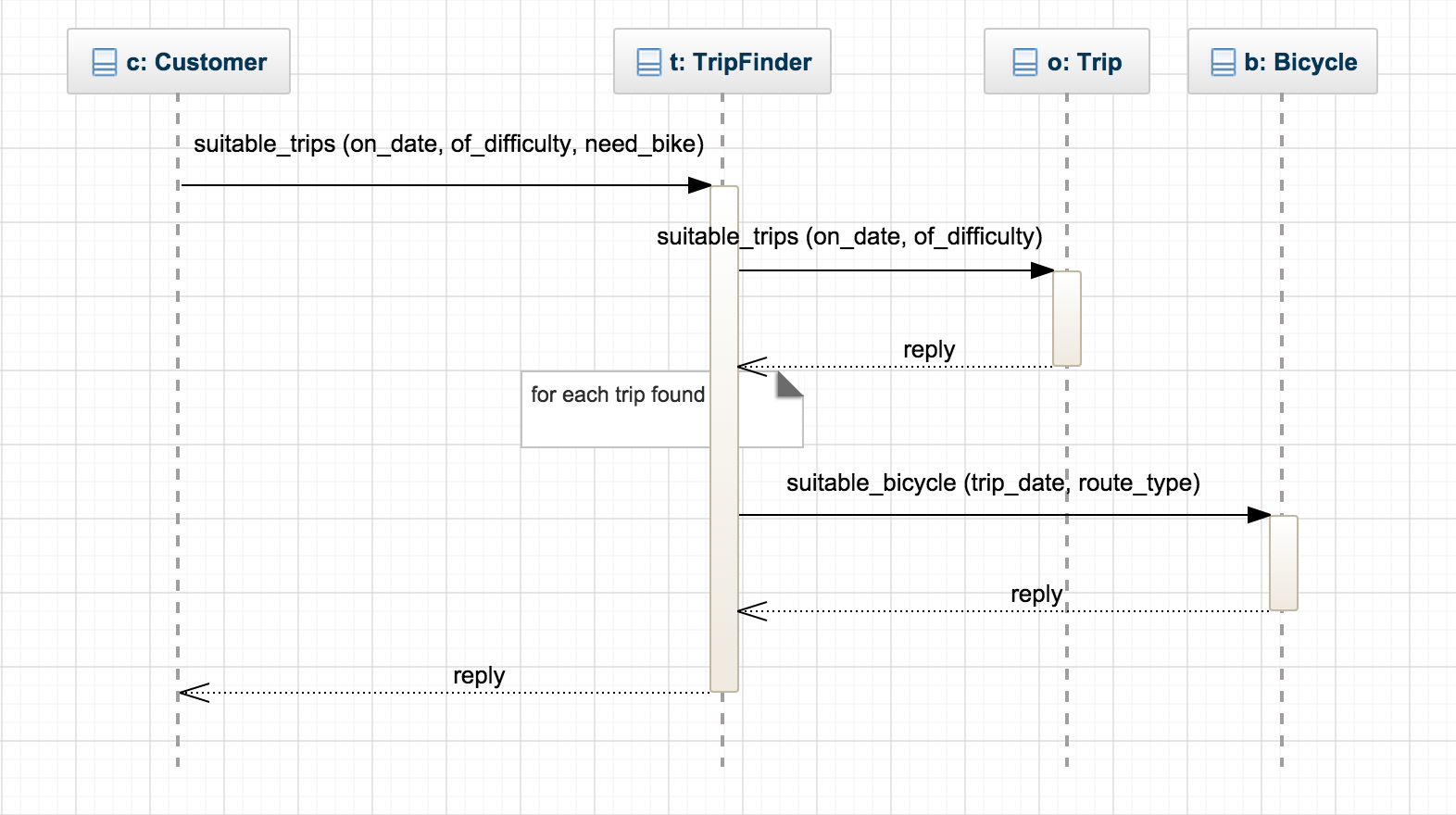

The new example for this chapter is a Bicycle Touring Company and the proposed use case is: A customer, in order to choose a trip, would like to see a list of available trips of appropriate difficulty, on a specific date, where rental bicycles are available.

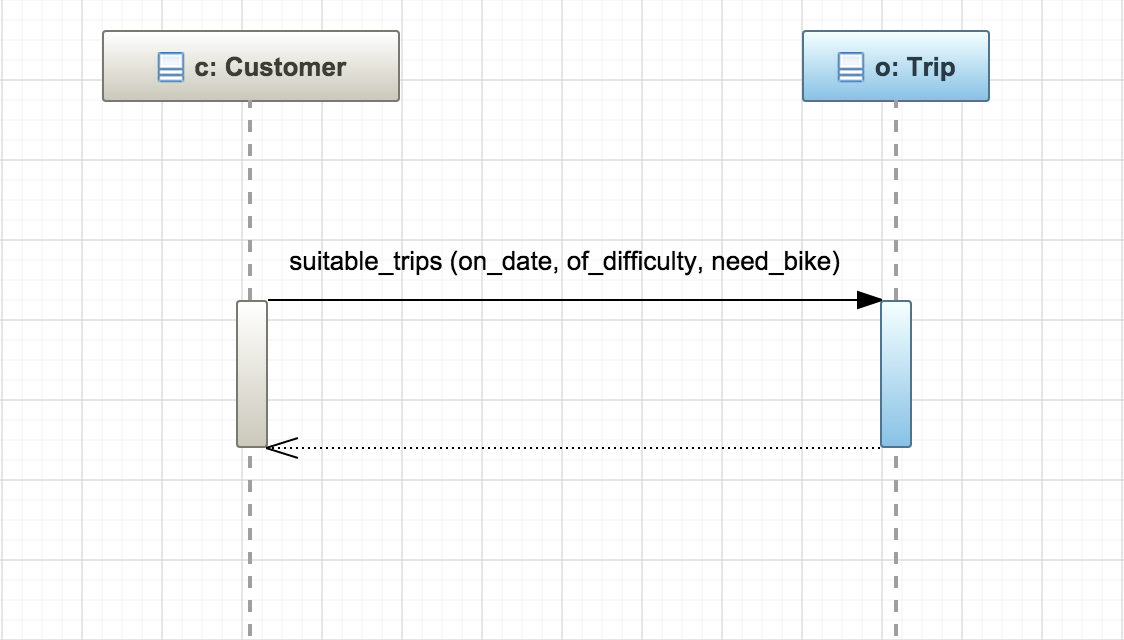

The word interface is used to refer to the kind of interface that is within a class. Classes implement methods, some of those methods are intended to be used by others and these methods make up its public interface. You probably expect to have Customer, Trip, Route, Bike and Mechanic classes. These classes spring to mind because they represent nouns in the application that have both data and behaviour. These are called domain objects. Using an UML (Unified Modeling Language) sequence as a new tool is introduced in this chapter. In the example below each object is represented by a box. It contains two objects, the Customer and the class Trip. Messages are shown as horizontal lines. When a message is sent, the line is labeled with the message name. Message lines end or begin with an arrow; this arrow points to the receiver. When an object is busy processing a received message, it is active and its vertical line is expanded to a vertical rectangle.

This transition from class-based design to message-based design is a turning point in your design career. The message-based perspective yields more flexible applications than does the class-based perspective. Changing the fundamental design question from “I know I need this class, what should it do?” to “I need to send this message, who should respond to it?” is the first step in that direction. In the above example it is reasonable for Customer to send a suitable_trips message but Trip probably should not be receiving the message.

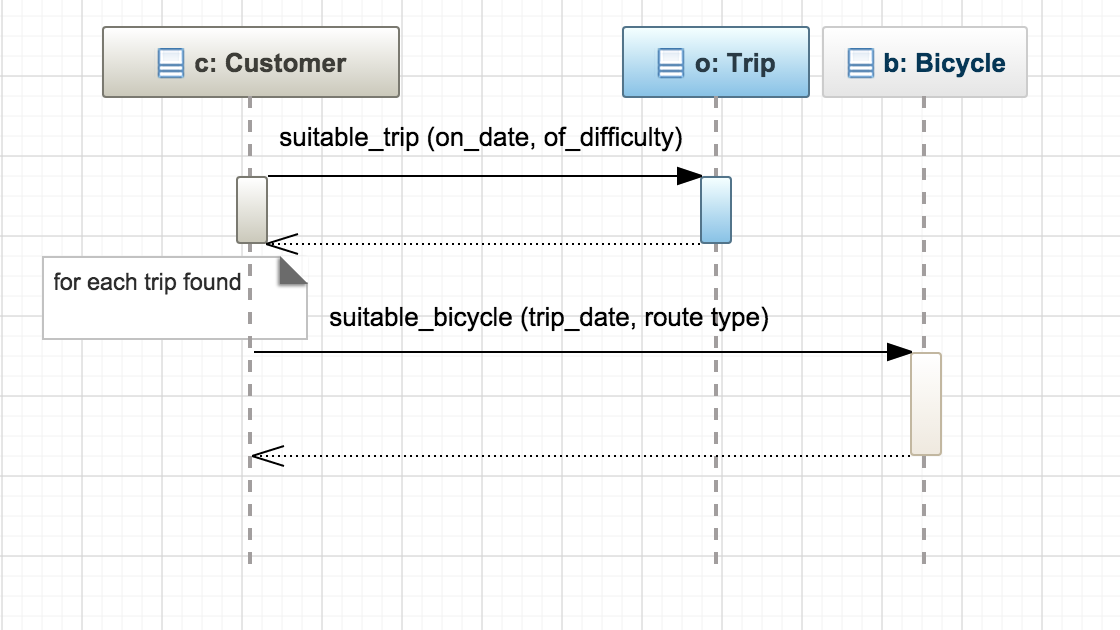

In the example below Customer knows that: 1. He wants a list of trips. 2. There’s an object that implements the suitable_trips message. 3. Part of finding a suitable trip means finding a suitable_bicycle message.

The problem is that Customer not only knows what he wants, he also knows how other objects should collaborate to provide it. The Customer class has become the owner of the application rules that assess trip suitability.

Asking for “What” Instead of Telling “How”

The distinction between a message that asks for what the sender wants and a message that tells the receiver how to behave may seem subtle but the consequences are significant. Understanding the difference is a key part of creating reusable classes with will-defined public interfaces.

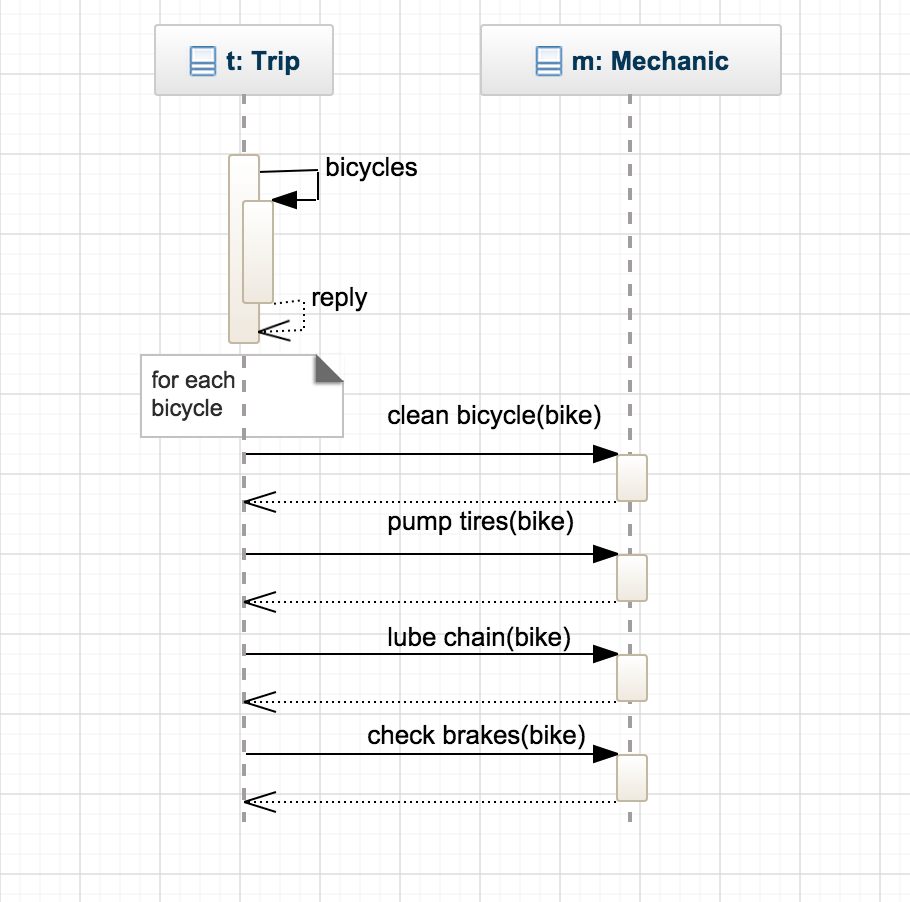

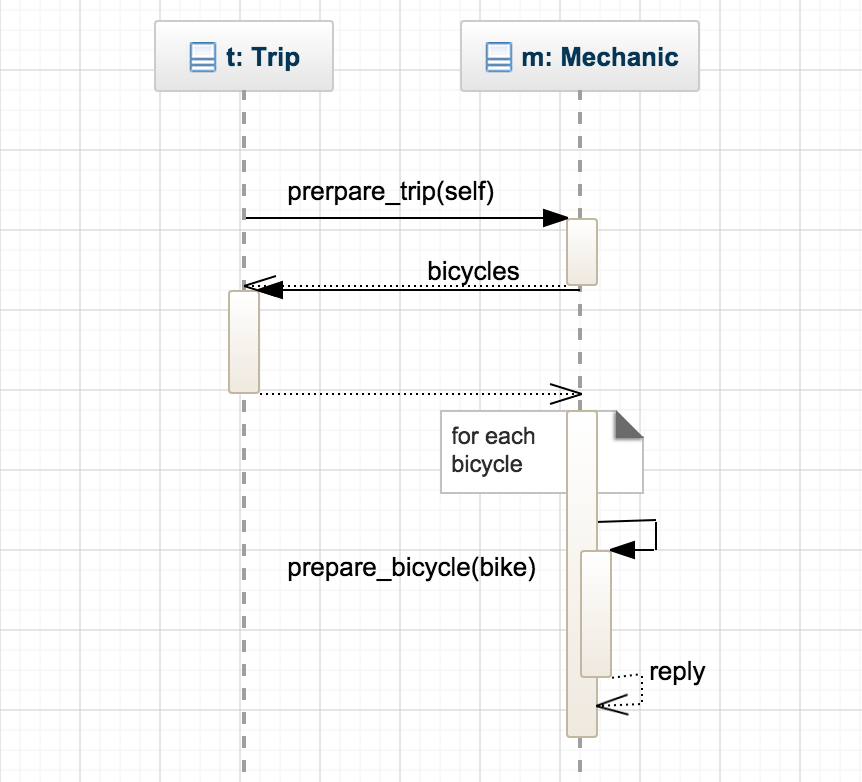

We will use a new use case to illustrate the “what” versus “how”: A trip, in order to start, needs to ensure that all its bicycles are mechanically sound. Trip could know exactly how to make a bike ready for a trip and could ask a Mechanic to do each of those things as illustrated in the next example.

A Trip tells a Mechanic how to prepare a Bicycle, almost as if Trip were the main program and Mechanic a bunch of callable functions. In this design, Trip is the only object that knows exactly how to prepare a bike; getting a bike prepared requires using a Trip or duplicating the code. Trip’s context is large, as is Mechanic’s public interface. These two classes are not islands with bridges between them, they are instead a single, woven cloth.

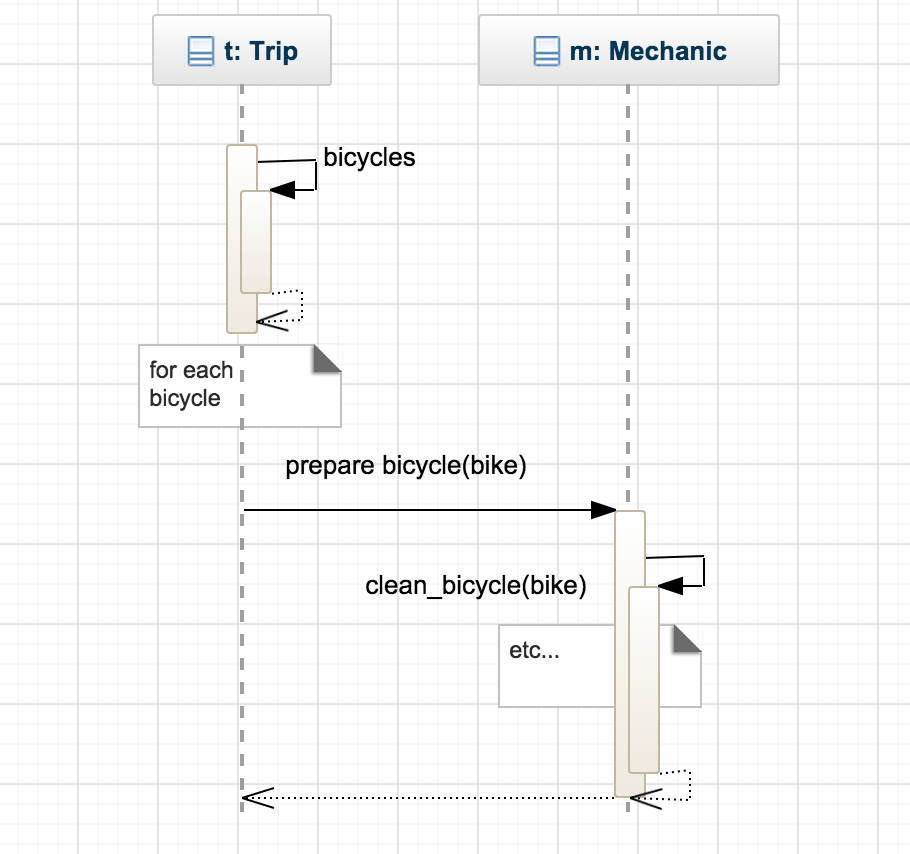

Here is an alternative where Trip asks Mechanic to prepare each <span class=”other-font>Bicycle</span>, leaving the implementation details to Mechanic.

This example is more object-oriented. Here, a Trip asks a Mechanic to prepare a Bicycle. Trip’s context is reduced, and Mechanic’s public interface is smaller. Additionally, Mechanic’s public interface is now something that any object may profitably use; you don’t need a Trip to prepare a bike. These objects now communicate in a few well-defined ways; they are less coupled and more easily reusable.

The next example illustrates a third alternative sequence diagram for Trip preparation. Trip tells Mechanic what it wants, that is, to be prepared, and passes itself along as an argument.

In this example, Trip doesn’t know or care that it has a Mechanic and it doesn’t have any idea what the Mechanic will do. Trip merely holds onto an object which it will send prepare_trip; it trusts the receiver of this message to behave appropriately.

Back to our original use case: A customer, in order to choose a trip, would like to see a list of available trips of appropriate difficulty, on a specific date, where rental bicycles are available. It is reasonable that Customer would send the suitable_trips message. That message repeats in both sequence diagrams because it feels correct. It is exactly “what” Customer wants. The problem is not with the sender, it is with the receiver. We have not yet identified an object whose responsibility it is to implement this method. We need a TripFinder, an object that contains all knowledge of what makes a trip suitable. It know the rules; its job is to do whatever is necessary to respond to this message.

Create Explicit Interfaces

The goal is to write code that works today, is reusable, and can be adapted for unexpected use in the future. Every time you create a class, declare its interfaces. Methods in the “public” interface should

- Be explicitly identified as such

- Be more about “what” than “how”

- Have names that, insofar as you can anticipate, will not change

- Take a hash as an options parameter

Be explicit with which methods are private and which ones are public to future-you and any other adopters of your legacy.

Honor the Public Interfaces of Others

Do your best to interact with other classes using only their public interfaces. The public methods will be more stable than the private ones. A dependency on a private method of an external framework is a form of technical debt. Avoid these dependencies.

The Law of Demeter

The Law of Demeter (LoD) is a set of coding rules that results in loosely coupled objects. Loose coupling is nearly always a virtue but is just one component of design and must be balanced against competing needs. Some Demeter violations are harmless, but others expose a failure to correctly identify and define public interfaces.

Demeter restricts the set of objects to which a method ay send messages; it prohibits routing a message to a third object via a second object of a different type. Demeter is often paraphrased as “only talk to your immediate neighbors” or “use only one dot.” Imagine that Trips depart method contains each of the following lines of code:

- customer.bicycle.wheel.tire

- customer.bicycle.wheel.rotate

- hash.keys.sort.join(‘, ‘)

Demeter became a “law” because a human being decided so, as a law it’s more like “floss your teeth every day,” than it is like gravity. Some of the message chains above fail when judged against TRUE:

- If wheel changes tire or rotate, depart may have to change. Trip has nothing to do with wheel yet changes to wheel might force changes in Trip. This unnecessarily raises the cost of change; the code is not reasonable.

- Changing tire or rotate may break something in depart. Because Trip is distant and apparently unrelated, the failure will be completely unexpected. This code is not transparent.

- Trip cannot be reused unless it has access to a customer with a bicycle that has a wheel and a tire. It requires a lot of context and is not easily usable.

- This patter of messages will be replicated by others, producing more code with similar problems. This style of code, unfortunately, breeds itself. It is not exemplary.

The first two messages are basically the same, one retrieves a distant attribute (tire) and the other invokes a distant behavior (rotate). Some would argue that violating Demeter to reach to a distant attribute as long as that attribute is not mutated is not much of a violation. The second violation points to the necessity for refactoring. Consider what this message chain would look like if you had started out by deciding what depart wants from customer instead of how it wants it. From a message-based point of view, the answer is:

- customer.ride

The ride method of customer hides implementation details from Trip and reduces both its context and its dependencies, significantly improving the design.

The third message chain, hash.keys.sort.join is perfectly reasonable and, despite the abundance of dots, may not be a Demeter violation at all. Instead of evaluating this phrase by counting the “dots,” evaluate it by checking the types of the intermediate objects.

- hash.keys returns an Enumerable

- hash.keys.sort also returns an Enumerable

- hash.keys.sort.join returns a String

If we accept that hash.keys.sort.join actually returns an Enumerable of Strings, then all of the intermediate objects have the same type and there is no Demeter violation. If you remove the dots from this line of code, your costs may well go up instead of down.